This post departs from our usual discussion of contract terms and talks about redlining and redlining software. A redline (sometimes called a “blackline”) provides a quick and easy view of the differences between a new contract draft and an old one. Usually, redlining software underlines added terms and strikes through (crosses out) deleted terms, but leaves the deleted terms legible. Redlining isn’t difficult, but doing it wrong can delay negotiations and even lead you to sign terms you didn’t mean to accept.

Almost everyone uses MS Word (there’s a monopoly for you), so I’m going to address Microsoft’s redlining system. In the newer versions of Word for the PC, you redline via the “Compare” button on the Review tab. In older versions and in Word for the Mac, you hit “Merge Documents” on the Tools menu. In older Word, it’s sometimes hard to figure out which doc the software will treat as the original and which as the revised version. Just look carefully and make sure the terms of the newer version appear as additions and deletions on top of the older one.

Almost everyone uses MS Word (there’s a monopoly for you), so I’m going to address Microsoft’s redlining system. In the newer versions of Word for the PC, you redline via the “Compare” button on the Review tab. In older versions and in Word for the Mac, you hit “Merge Documents” on the Tools menu. In older Word, it’s sometimes hard to figure out which doc the software will treat as the original and which as the revised version. Just look carefully and make sure the terms of the newer version appear as additions and deletions on top of the older one.

Here are six rules for good redlining:

- Get to Know Your Redlining Software. If you’re not intimately familiar with the redlining feature of your version of Word, play with it. Run test redlines and study them. That’s worth more than a month of law school, and it costs less.

- Don’t Create a Redline on Top of a Redline. Redlining works best when it’s two-dimensional: when you’re comparing two versions of a contract. Comparing three versions—comparing the current version to the last one and the one before that—will create a document too complicated to review. Yes, you might try and simplify a “triple redline” by assigning different colors to different versions, but that rarely leads to a legible comparison. Plus, you don’t gain much by comparing three versions. In most contract negotiations, nothing matters but the difference between the last version and the current one. So when you’re drafting, don’t use the “Track Changes” feature to add your redlined changes on top of the other party’s redline, creating a comparison of three docs. (See point 5 below re Track Changes.) Work on a clean copy of the other party’s last version. Or use the other party’s redline but go through and accept the changes you like and reject the ones you don’t, using “Accept” and “Reject” buttons in Word (near the Merge Documents or Compare button). By the time you’re done accepting, rejecting, and otherwise revising, you should have a clean copy with the language you want and nothing from older versions. Then run a redline comparing that to a clean copy of the other party’s last version.

- Don’t Read Triple Redlines. Along the same lines as point 2 above, don’t get yourself confused trying to read a triple redline: a redline that compares three versions. Instead, run your own redline, comparing the clean copy of the other party’s revised version against your own last version. Or if the other party didn’t send you a clean copy, just hit “Accept all Changes” (near the Merge Documents or Compare button) to create a clean version of the other party’s work. Then run a redline, comparing that to your last version. (I sometimes circumvent the whole problem by sending my redline as a PDF, alongside a clean copy in Word. That way, the other party can’t edit the redline—can’t create a triple redline—and has to work off the clean copy.)

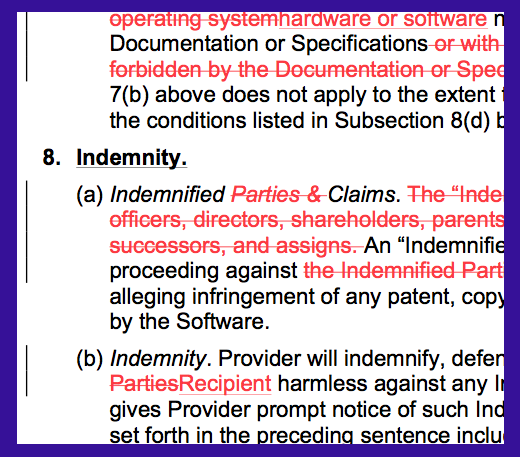

- If You Have Doubts about the Accuracy of the Other Party’s Redline, Run Your Own. You’d be surprised how often the other party sends me a redline that doesn’t match the other party’s clean copy. For instance, my proposed indemnity clause gets deleted from both the clean copy and the redline, but the deletion isn’t struck through in the redline. The language is simply missing, so if I’m just reviewing underlined additions and struck-through deletions—which is the whole time-saving point of a redline—I won’t notice the change. In almost every case, the problem results from carelessness rather than dirty tricks, but that won’t help you if you sign the wrong terms. You can avoid the problem by running your own redline: comparing your last version to a clean copy of the other party’s new one. And again, if you don’t have a clean copy of the other party’s new version, hit “Accept all Changes” to create one.

- Don’t Rely on “Track Changes.” MS Word’s “Track Changes” feature redlines as you revise a document. Track Changes works fine for limited revisions drafted quickly, like in a single sitting. But it doesn’t create a clean version of the contract, and it can get screwed up if you’re reworking the same language over and over. In general, I recommend that you avoid Track Changes. Instead, create a clean new version of the contract and then run a redline against the old version.

- Change as Little as Possible. A redline draws the other party’s attention to every change you make. So the less you change, the more reasonable you’ll seem—and the less work you’ll impose on the other party. If you want your negotiation to move along quickly, don’t change anything that doesn’t really matter. Some grammatical errors impact meaning, but many don’t. The same goes for run-on sentences, poor construction, passive language, and all the other boogeymen haunting the legal world. Avoid them in your own drafting, but don’t fix them unless they impact the contract’s meaning in a way that hurts you. We’re creating a business tool here, not a work of art. The fringe benefit is that a light redline will make the other party happy, and happy negotiators tend to be flexible.